How To Talk Comedy Writer – Updated!

A couple of years ago, I put together a list of weird little bits of terminology that comedy writers use. Only a few of these can be found in books about writing – most are terms that have grown out of writers’ rooms, email exchanges, and talking shop in the pub. Some are in wide use: others used by literally only a couple of people. I’ve just been told a lot more of them so the list has grown, a lot. Please enjoy.

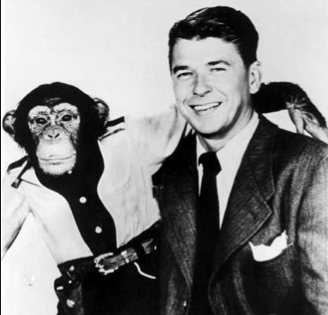

Langdon – a joke construction named after the writer John Langdon, who loves to write them. The stages of a Langdon are: (i) two elements are introduced. (ii) It appears that we’re continuing to talk about one of those elements in particular… (iii) but then it turns out we were talking about the other one. A 1980s-style example should make it clear. “Ronald Reagan met a chimpanzee today. The simple, gibbering creature… was delighted to meet a chimp.” Pete Sinclair tells me he’s been using that example to explain Langdons since it was current. And he likes to get at least one Langdon a week into Have I Got News For You.

The Yes (No) – via Ian Martin. A dialogue trick he picked up from Tony Roche, Simon Blackwell and Jesse Armstrong while writing for The Thick Of It. The character says yes but the in-parenthesis says no. So we know that they know they’re lying. A: “You didn’t lose those figures, did you?” B: (yes) “No.”

Send that through to Wording – When you’re writing in a room and you’ve collectively got the shape and structure and comic idea of a gag or scene in place, but it needs writing up/rewriting. Via Simon Blackwell, used while on the Have I Got News For You team. Simon likes the idea of there being a separate Wording department, probably paid less than the writers.

Lightning Rod – a joke put into a script which is deliberately controversial, tasteless or offensive, and designed to attract discussion and worry from producers, executives and (in the US) the Standards and Practices department. The lightning rod will be fretted over and eventually dropped, which is fine… because its true purpose was to deflect attention from another, only slightly less offensive joke which you really want to make it through. Jason Hazeley calls the same thing a ‘Queen Mum’, derived from a joke about the Queen Mother being pregnant which Chris Morris put in a Brasseye script as a hostage to fortune. [via Ed Morrish]

The Tesbury Rule – don’t confect an unconvincing commercial brand name in a script when you mean, for example, Tesco or Sainsbury; it weakens the gag. [via Jason Hazeley]

Gags Beasley – a useful name to invoke when a script needs some solid boffo old-school punchlines. As in “Paging Gags Beasley” or “Can we get a Gags Beasley pass?” It’s derived from the name of Fozzie Bear’s joke writer, who was occasionally mentioned, but never seen, in the Muppet Show. [via Sarah Morgan]

Fish Business – a quick set up, so the story hits the ground running. Invented by Laurel & Hardy. They begin Towed in the Hole, 1932, with the line ‘For the first time in our lives we’re a success – nice little fish business, and making money.’ Hollywood seized on this and throughout the 30’s and 40’s producers would throw first drafts across their desks at writers snarling ‘needs better fish business.’ [via Julian Dutton]

Eating The Sandwich – an expression used by Jesse Armstrong and Sam Bain, inspired by a memorably bad scene they read in a script once: a character drugged a sandwich with some sleeping pills and while on the way to deliver it, forgot, took an absent-minded bite, and passed out. Any time a character seems to be directly causing their own problems in a rather contrived way, they’re ‘eating the sandwich.’ More external pressure is needed to make them do something funny.

Gorilla – a plot point or joke which the audience will remember after the show is finished. Any given show would benefit from one of these. Derived (it’s thought) from a theatre piece where a gorilla appeared at a very pleasing point, so everyone went home talking about the gorilla. For writers, it’s worth bearing in mind that some of the greatest gorillas in British sitcom – Brent’s dance, Fawlty thrashing the car, Del falling through the bar and Granddad dropping the wrong chandelier – are primarily visual experiences, not dialogue-based. [via the Dawson Bros, Gareth Edwards and Stephen McCrum]

Factory Nudgers – what the great (sadly late) writer Laurie Rowley called memorable comedy moments. The principle being that if a bit in a show was sufficiently funny, people at work the next day would nudge each other to quote or re-enact it. So more or less like the gorilla, but harking back to a pre-video age where Britain watched the same shows at the same time, and there were a lot of factories. Laurie had a strong Yorkshire accent, so imagine how great it sounded when he said ‘factory nudgers.’ [via Alan Nixon]

Vomit Draft – AKA ‘Puke Draft’ AKA ‘Draft Zero’ – The very very first draft of a script, which is almost certainly not shown to anyone. It’s invariably full of typos, misfired jokes and logical flaws. Only when the writer has cleaned it up a bit can she/he bear to send it to the producer. This is in quite common use. But Katy Brand has a different meaning. Her Vomit Draft is the second one; based on the Biblical saying from Proverbs verse 26, ‘as a dog returns to its vomit, so fools repeat their folly.’ Not a bad description of the rewriting process.

Red Dot – named after Apple’s tamper-proofing. Adding a reference to someone – e.g. a minor character name – to check that person has really read the script. [via Jim Field Smith]

Detonator Word – the key word that reveals the joke – which should be as close to the end of the punchline as is linguistically possible. [via John O’Farrell]

Scales – the first hour or so on a writing session, when everyone’s flexing their muscles, usually with the most inappropriate and unbroadcastable material. [via Jason Hazeley]

Turd in a Slipper – a joke which feels good, but isn’t really any good. [via Judd Apatow]

Jazz Trumpetry – the extra, unneeded punchline that comes after the punchline you should’ve finished a sketch or scene on. It comes from the Brain Surgeon sketch which the Dawson Brothers wrote for Mitchell and Webb. The original draft was road-tested at (they think) London’s tiny Hen and Chickens theatre, where they had a joke where a rocket scientist comes in and says “Brain Surgery? Not exactly Rocket Science.” Big laugh. But they’d written an extra line after that, where a Jazz trumpeter comes in and finishes his line with “Rocket Science? That’s not exactly Jazz Trumpetry.” It tickled them to write it, but at the test out night, no laugh at all. So Jazz Trumpetry was cut from the final sketch that got on air – and ever since, has been the Dawson Bros’ shorthand for misjudged bonus punchlines. [via Andrew Dawson]

Bananas on Bananas – similar to Jazz Trumpetry. Trying to top a punchline with another punchline right after it, and another, and another. Sometimes this might be great – but when it’s not, and the result is just tiring to watch/read/listen to, then you’ve got Bananas on Bananas. [via James Bachman and Simon Blackwell]

Jengags – as in ‘Jenga gags’, i.e. too many gags piled on top of each other. Same thing, really, as Bananas on Bananas. [via Laurence Rickard]

Jenga Jokes – same meaning as Jengags. This version used by Julian Barratt and Noel Fielding. [via Alice Lowe]

Load Bearing Pun – one word carrying the whole damn misunderstanding. [via Al Murray]

Character Gibbons – when writing for Green Wing, Oriane Messina and Fay Rusling talked about ‘character gibbons’, which are basically ‘givens’ but misheard early on in their careers as gibbons. They still refer to the gibbons when developing scenes, character, plot etc. [via Oriane Messina]

Malt Shop – when me and Kevin Cecil were starting out and didn’t know fancy words like ‘epilogue,’ this was how we talked about the short scene at the end of a story when the climax has passed, a couple of loose ends are tied up, there is a final joke, and then that’s the end. It’s from the first few series of Scooby Doo, when the gang typically ended up in the malt shop at the end of each episode. We still use this word all the time, in preference to epilogue.

Mururoa – a subject that you just can’t write a gag about because the word itself just won’t sit within the rhythm of a joke. This one’s from John O’Farrell. When he was writing comedy monologues in the 90s, there was an ongoing news story about the French doing nuclear tests on Mururoa Atoll, but he discovered that the place name just has all the wrong letters to be used in a punchline (i.e. the opposite of Cockermouth).

Gag desert – the bit of comedy script which goes on for too long without a joke. [via John O’Farrell]

Group 4 – a subject that is held in such public ridicule that just mentioning it in a topical show can get you a big laugh. Group 4 Security used to get this reaction on Have I Got News For You in the 90s, as did the M25. In the run-up to the 2012 Olympic Games, it was the G4S security firm (AKA the renamed Group 4). Going back to the early 90s, Ratners (the jewellery shop) was the comedy touchstone. Still further back in the late 70s/early 80s, it was British Rail, and even more specifically, the British Rail pork pie. Group Fours which never seem to go away: Pot Noodle, and Sting’s tantric sex. [via John O’Farrell]

Grand Maison – something you’ve made up for the sake of the punchline. In one sense, everything in a script is a Grand Maison; but the term is just used to describe the moments when it feels forced and contrived. From a sketch containing the following exchange:

BARISTA: And would you like that piccolo, medio, or Grand Maison?

CUSTOMER: Grand Maison? That sounds like a big French house!

This comes via Ed Morrish, heard from Jon Hunter. Dan Harmon has a similar term: Monopoly Guy. He derives this from the second Ace Ventura film, where Ace insults a man who just happens to look like the Monopoly guy by calling him ‘Monopoly guy.’

Logic Police – when there is a logical flaw in a script which is significant enough to cause problems, somebody – an actor, producer, director, script editor, or the writer him/herself – must appoint themselves the ‘logic police’ and point it out. It’s no fun, being logic police; your intervention might mean junking a joke, a scene, or even a whole storyline which people like. It’s an ugly but necessary job.

The F***ing Crowbar – cramming in an F-bomb before the final word(s) of a punchline for added pizzazz. Normally effective, but a soft indicator that the joke isn’t one of the best. [via @smilingherbert]

Garden Birds – denotes an unnecessary bit of explanation after the punchline has been delivered and everyone has got the gag. John O’Farrell’s grandfather had a pre-war joke book, with one tortuous tale about an outraged radio listener writing to the BBC after he’d heard the phrase ‘tits like coconuts.’ The BBC’s reply informed him that if he’d continued listening he would have heard ‘while sparrows like breadcrumbs for the talk had been of garden birds’. The laugh is on ‘breadcrumbs’, you don’t need to explain any further.

Baroqueney – pronounced ‘baroque-knee.’ A combination of ‘baroque’ and ‘cockney.’ This is a style of dialogue which came riding hard into British cinema at the end of the nineties, in the films Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, Gangster No.1 and Sexy Beast. Cockney villain talk, but full of as many interesting verbal images, surprising similes and inventive insults as you can cram in. Me and Kevin Cecil parodied it when writing the part of the East End Thug, a part played by Alan Ford in The Armando Iannucci Shows. The Fast Show did a great spoof of it too, called ‘It’s a Right Royal Cockney Barrel Of Monkeys.’

Ruffle – an aspect of a joke (a name, or reference) which is getting in the way and making things less clear. In the script editing process for the BBC2 chef comedy ‘Whites’, there was a reference to a character called Jamie, which made you think of Jamie Oliver. That was a ruffle, so it went. [Via Simon Blackwell]

Bicycle cut – aka the bicycle joke, or a ‘Last Of The Summer Wine.’ A character ends a scene by firmly stating that they will not do a certain thing – for example, riding a bike. The next scene begins with that character doing that thing. Roy Clarke wrote tons of these for Compo in Last of the Summer Wine. “You’re not getting me in that thing with wheels and no brakes!” Cut to Compo, poised to go downhill in that thing with wheels and no brakes. Dave Gorman calls the same thing the B.A. Baracus, as in “I ain’t gettin’ in no plane!”… cut to B.A. in a plane. [via Graham Linehan]

Gilligan Cut – a common American term for the bicycle cut. Derived from ‘Gilligan’s Island.’ The term Gilligan Cut is never used in the UK because Gilligan’s Island has only been shown very rarely, and even then not in all regions of the country.

Foggy Says He Knows The Way – a joke construction, something like the mirror image of the bicycle cut. In the nineties, when Kevin Cecil and I were writing for The Saturday Night Armistice (AKA the first series of The Friday Night Armistice), we spent a couple of days working in a room normally used by the production team of Last Of The Summer Wine. The best known story from that week has been related by Armando Iannucci in interviews from time to time. A large board was covered with cards detailing Summer Wine plots; Foggy does this, Compo does that. I began adding cards with scenes like ‘Compo bursts puppy with cock’ and ‘Compo finds the body of a child in a burned-out car.’ But I also remember two cards in particular (not ones I added); ‘Foggy says he knows the way,’ followed by the scene ‘Foggy gets lost.’ For me this encapsulated a very elemental comic building block. Character confidently says they can do something; character tries but fails to do that thing. Most scripts, somewhere in them, have a ‘Foggy says he knows the way’ bit.

The Deja Vu Closer – – referring to the subject of a joke earlier in the set within the final joke. A stand up tool, more than a scriptwriting one. [via @SmilingHerbert]

Chutney – stuff that characters are saying in the background, which you don’t normally add into the script until very late because it’s not material which needs jokes. Writing for Veep, chutney often takes the form of perfectly serviceable political speeches, while the real funny material is going on amongst other characters in the foreground. I don’t know if this term exists outside the Veep/Thick Of It writing team.

Scud – a joke that ends up getting the wrong target. E.g. “the energy companies have done some truly appalling things– one of them based itself in Newport.” The punchline is saying that Newport is shit, and not saying anything about the energy companies. Named after the outdated and inaccurate Soviet missile used by Iraq during the 1991 Gulf war. [Via Pete Sinclair]

Lampshading – addressing a flaw, recurring trope or plot hole by having a character point it out. There’s a nice example of lampshading in the book of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Just after Violet Beauregarde has been maimed by Wonka’s chewing gum, and the oompa loompas have sung about what a terrible thing chewing gum is, one of the parents asks Wonka: if it’s so bad, why are you making it? Wonka gives a short evasive answer, then the story moves briskly on. [via David Simpkin]

Frampton Comes Alive – in a sitcom written by Steve Punt and Hugh Dennis, the script editor wanted them to change a reference to Pete Frampton’s ‘Frampton Comes Alive’ (as an embarrassing album to have owned) to ‘Saturday Night Fever.’ So Steve and Hugh use it to mean a situation when a niche example will be really funny, but only to a small number of people, as opposed to a mainstream example which everyone will know, but which isn’t funny.

F.I.T.O. – stands for ‘Funny In The Office’ – a joke that gets a big laugh at the read-through in the production company, but only because of some in-joke or particular reference that won’t play outside the room. [via John O’Farrell]

Two Sock – when you find yourself using two jokes/motivations/expositions, when only one is necessary. [via Kieron Quirke]

Hat On A Hat – this is in very common use in the USA, and has a similar yet subtly different meaning to ‘Two Sock.’ A Hat On A Hat is an occasion where two funny things are happening at the same moment in the script, or immediately adjacent moments, and those two comic ideas are each distracting from the other. The solution is normally simple: remove one of them.

North by Northwest Gag – Prop introduced at beginning of scene, which stays in shot. Later used to pay off a joke after audience have accepted, then forgotten, its presence. [via @richardosmith1]

Fridge – the piece of paper, noticeboard, book or computer file where you put the jokes you cut for whatever reason, but which may work in another time and place. ‘Fridge’ came from Gareth Edwards, but lots of writers have different names for the same thing. Sarah Morgan has a ‘bottom drawer.’ Dave Cohen has a ‘shoebox.’ Greg Daniels calls it ‘the sweetie bag.’ When writing “In The Loop,” Tony Roche, Simon Blackwell and Jesse Armstrong called theirs ‘the fun bucket.”

Doofer – Paul Bassett Davies says his mother and her friends used this word in the second world war, to describe a saved half-smoked cigarette that will ‘do for later.’ For Paul, it’s a gag he’ll use later. So, a good example of the sort of thing you’d put in the Fridge (see above).

The Restaurant on the Corner – (American) – a bit in a script where no matter what joke you put there, its still never quite works. Also called a ‘Bono’, after a restaurant opened by Sonny Bono in West Hollywood. It shut quickly, as did every other restaurant which opened on the same spot. Writers working nearby decided the corner must be cursed. If you have a Bono in a script, it will be a gradual realisation, because it always feels like something SHOULD work there, and you might try a dozen or more things before the truth dawns. You can only deal with a Bono by taking apart and rebuilding a larger section around it – probably the whole scene, maybe even a bit more. [via Dave Cohen]

Killing Kittens – removing jokes which you really love, because they’re getting in the way of the story. [Chris Addison]. Also known as ‘stripping the car.’ [Joel Morris]

Bucket – strong, simple idea to contain all the nonsense you want to put in. ‘Parody of air disaster film’ is a great bucket. [Joel Morris]. Not related to ‘fun bucket.’

Oxbow Lake – the rewriting process produces these. A bit in a script which used to have some plot/character importance, but as the story has changed around it, no longer has a purpose. You have to remove it on the next draft. Sam Bain and Jesse Armstrong use this term. Me and Kevin Cecil call them ‘hangovers.’

Rabbit hole – a fact you check on the Internet and that’s the rest of the morning gone. [John Finnemore]

Joke Impression – a line that sounds like a joke, and has the rhythms of a joke, but isn’t actually a joke. Also known as ‘hit and run’, ‘joke-like substance’ or ‘Jokoid’ [John Vorhaus, from his very good primer ‘The Comic Toolbox’]. A joke impression has its uses. When you are thundering down a first draft, and are more concerned about the overall structure than individual jokes, you can slot in a few joke impressions at spots in the script where a good joke is hard, in the full knowledge you can come back later and fix them. I’ve been told of a more aggressive use for them too. I was told that when Jim Davidson knows one of his writers will be in the audience, he picks out one joke which is clearly a dud, a joke impression, and tells the writer he’s going to deliver it anyway and make the audience laugh – even though it doesn’t make any sense. The subtext: Jim is saying “I’m the one who brings the magic, not you.”

Fridge joke AKA ‘Refridgerator Logic’ – related to the joke impression. The audience realise they laughed at something that didn’t actually make sense, but much later, when they are (for example) getting something from the fridge. [via David Tyler]

On The Nose – very widely used, this one. A line which is on the nose is just too clumsily obvious, too direct, and lacks subtext.

Gerbeau – a joke that literally nobody but you is going to get, but it does no damage, so it stays in. Derived from “please yourself,” which shortens to ‘P .Y.’, Which then becomes Gerbeau after P.Y. Gerbeau, the guy who ran the millennium dome. The term Gerbeau is itself a nice example of a Gerbeau. [Via Joel Morris]

Two Percenter – similar to the Gerbeau. Only two percent of your audience will get it. [via Jane Espenson and Dave Cohen]

Plotential – and the idea or situation which has the potential to be developed into a full-blown plot. As in “does this idea have plotential?” [via Sam Bain – though he does stress that he and Jesse Armstrong are mostly taking the piss when they say this in conversation]

Nakamura – The most nightmarish of writer’s problems. It’s when there’s a huge issue with a script which effectively means that the whole thing is holed below the waterline. This derives from the writing team for The Odd Couple, who once hinged a storyline on the highly doubtful premise that the name ‘Doctor Nakamura’ was intrinsically hilarious. Come the day of the record, the studio audience sat silently through all the Nakamura material.

Nunya – a work at an embarrassingly unready stage. If anybody asks about it, you say “nunya business.”

Cut and Shut – a term borrowed from the motor trade (welding two halves of two cars together). This refers to a conceit which is essentially two normally incompatible ideas, bolted together. An example: Big Train’s cattle auction, where they are not cattle, they are new romantics. (via Jason Hazeley)

Frankenstein Draft – a script that suffers over time from bolting on too many slavishly implemented notes.

Frankenstein (verb) – Joining already-written scenes together in a highly inelegant way. You know it’s not pretty, but it’s a temporary tool which might give you some idea how the completed sequence might work. Frankensteining is very common when writing animated movies, in which the scripting is often done alongside storyboarding. [Andy Riley]

Pitcheroo – anything which reads well in a pitch document or story outline, which you know won’t quite hold water when you are writing the actual script. But very handy if you’re up against it time wise, and you need to convey what it is you’re intending to write, but you haven’t got the hours to crack every single story beat. An example might be “They escape from the party, and then…” How do they escape from the party? Won’t they need an excuse, or will they climb out the window? Who knows? You know you’ll need to cover that in the end, but so long as it’s followed up with a funny idea in the second half of that sentence, you can get away with it for now. Because most people read pitches and story outlines much too fast, effective pitcheroos are never spotted. [Andy Riley/Kevin Cecil]

Gooberfruit – when you’re a British writer, and you’re writing a script set in America with American characters, some words need to change. Some of them everybody knows; lift becomes elevator, pavement becomes sidewalk. But sometimes you’ll realise, as you’re scripting, that a British word probably has a different American word which you can’t quite recall. You might not want to interrupt your writing flow by diving into google at that moment, so best write the British word, pin it as a ‘gooberfruit’ – a word needing US translation – and carry on. You can come back to it later. Derived from the tendency of fresh groceries to go under different names in America; eggplant for aubergine, zucchini for courgette, etc. [via Andy Riley and Kevin Cecil]

Bull – coined by Sid Caesar. A line which diminishes the speaker’s status, against their intent. Example: “I don’t need anybody to help me look stupid.” (Via Paul Foxcroft)

Laying Pipe – this one’s commonly used in America. It means planting the exposition which is necessary for the audience to understand what’s going on. This can be done elegantly; like in Monsters Inc, where the first 15 minutes of the movie lays out a mass of exposition about how the monster world works, but all with scenes which also advance the story and have jokes in. Or it can be done bluntly; like in Looper, where the complex rules of the world are explicitly laid out in voice-over.

Shoe leather – similar to laying pipe.

Crossword clue – a joke based on a brilliant verbal trick or pun… At which nobody laughs. [via David Tyler]

CBA – Meaning “could be anything.” [via Graham Linehan] A joke where a key component is interchangeable with many other options. Many Victoria Wood jokes referencing brand names are CBAs.